This blog was first published on the HEA website at : HEA Blog: The role of scholarship of teaching and learning in developing practitioner /academic identities

All faculties employ individuals who have made the move from practitioner, to academic: Whether teacher, business leader, lawyer, social worker or nurse, very often these individuals have attained seniority in their professional lives. Yet the literature on this transition illustrates that it is rarely straightforward. The move has implications for values and purpose whilst prior assumptions on academia can create a great deal of cognitive dissonance for the individual.

Pedagogical research or the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) is now a feature of the higher educational landscape, brought about in no small measure by policies that place a premium on evidence-based practice and knowledge exchange. Having employed SoTL as a mechanism to craft my own professional identity I discuss how SoTL can aid practitioner/academic transition, helping individuals make sense of their work and feel part of valued communities of practice.

Hankering for the past when the present doesn’t satisfy

Concepts and beliefs about professional identity are wide ranging – from the arguments that identities are relatively fixed, to those that regard them as work in progress, malleable and adaptive. My own work over the past 15 years on this adopts the narrative perspective,(Connelly, 1990) in which individuals make sense of their environment by carrying out identity work and creating and re-creating a rhetorical history that suits their purpose (Suddaby et al., 2016; Taylor, 2005). This approach also considers the field of organisational identity creation and the ways that individuals establish credibility within a field or role (Baxter, 2010, 2011; Baxter, 2012; Baxter, 2013).

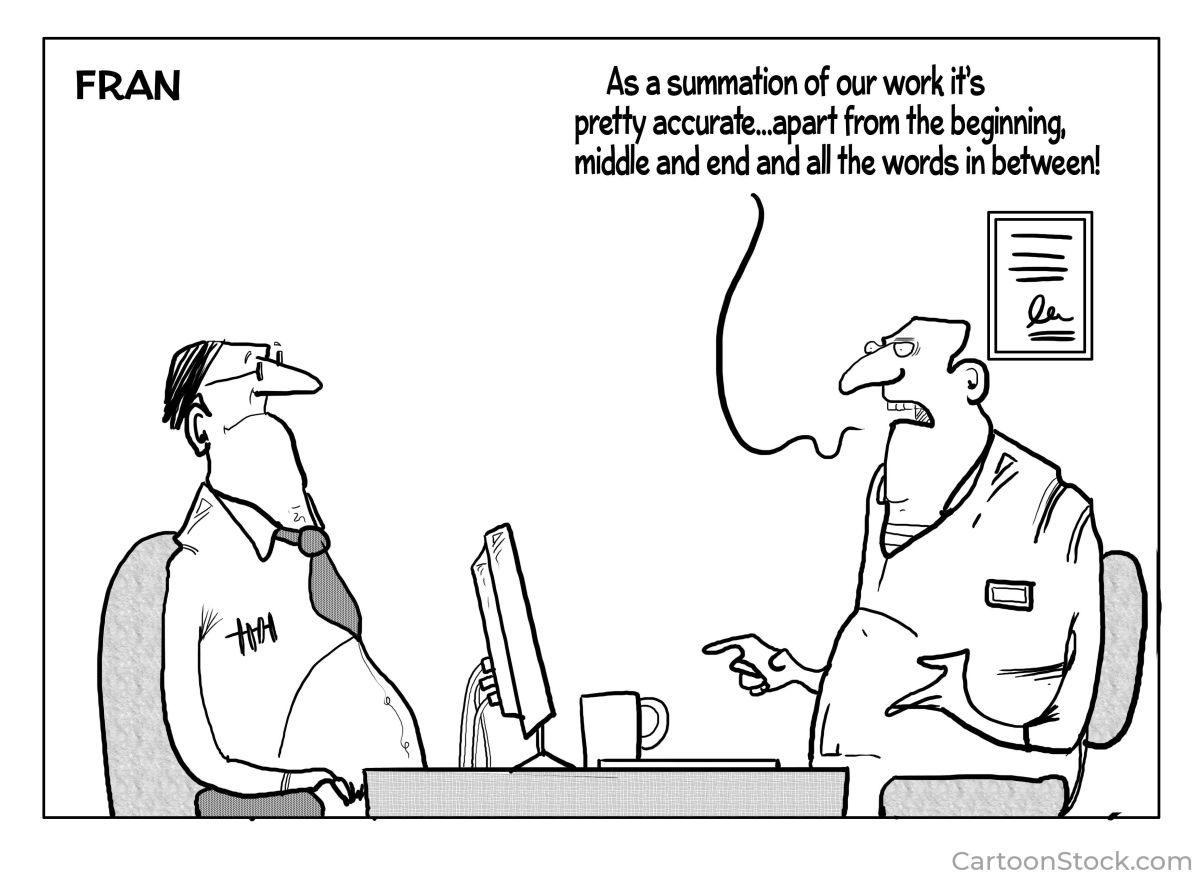

Transitions in HE are further complicated, due to the fact that there are so many ways to become and be, an academic – many practitioners even chafing at the term ‘academic’ as being a role that is divorced from the ‘real world’. In addition, we all enter HE complete with assumptions about what it means to be an academic. Once in post the challenges are myriad, ranging from the adaptation of value systems and norms (rarely explicit) to different status, authority, and accountability to that experienced in former roles. Bruce Macfarlane’s recent paper, offers a tongue in cheek account of some of the drivers and beliefs underpinning academic identities (Macfarlane, 2022). His diagram (figure 1 page, ), illustrates islands of practice on which the academic may find themselves, and the numerous different priorities and beliefs that drive and shape this nebulous role.

The cost of identity failure

The cost of not being able to find a way to ‘be’ in HE is high, and can result in lack of team spirit, mental illness, and finally attrition, as individuals return to former comfort zones in order to retain their equilibrium and sense of ‘self’, and autonomy (Chen et al., 2022). This autonomy, or lack of agency is characterised by low motivation, and can easily overlap into an individual’s personal life and worldview. As Boyd and Harris put it, ‘new lecturers are seeking credibility through knowing and constructing their pedagogy, but they pursue this within a complex and confusing context that involves a considerable amount of boundary crossing and uncertainty’. So how can SoTL help with this identity work ?

Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL)

Individuals crossing over from any field, to academia often report they find it easier to create identities in relation to teaching and interface with students, this is particularly so for those on teaching contracts only who may come into academia without doctorates or much experience of research (Handley, 2005) Even if they have no research within their contracts, their natural curiosity can drive them to carry out SoTL research. So what can this offer them in relation to their professional , academic identities ?

SoTL explorations can range from investigations based on a ‘what works’ approach, straddling quality assurance/research, to theoretically robust scholarship which draws on theories and concepts of learning and engagement. For teachers, this allows them to investigate their own practices and concomitantly themselves, by exploring their area of interest in relation to other practices, other research accounts, other pedagogies and fields of thought.

Crafting and creating academic credibility

Teaching is a rewarding but sometimes frustrating occupation and despite our best efforts, students can and do disengage. Carrying out SoTL permits individuals to become more empowered by their research, engaging with others and creating narratives inherent within professional interest communities (Brown, 2006). This not only has the power to make them feel part of communities of practice, but moves them from the periphery to centrality, within these communities, a move known to contribute to both professional agency and expertise (Lave et al., 1991).

Sadly, in many HEIs this research is often thought of as somehow not as powerful or transformative as traditional research. In my view, institutions need to think more creatively about this research and how to incorporate it within their practice, or risk lack of professional job satisfaction and attrition amongst ex practitioners. In addition, in light of the recent policy agenda on impact, engagement and knowledge exchange, failure to do so threatens not only the academic community within the organisation, but the very organisation itself.

References:

Baxter, J. (2011). Public Sector Professional identities: etiolation or evolution; a review of the literature. . from http://oro.open.ac.uk/29793/

Baxter, J. (2012). The impact of professional learning on the online teaching identities of higher education lecturers:the role of resistance discourse European Journal of Open,Distance and E-Learning, 1(2).

Baxter, J. (2013). Professional inspector or inspecting professional? Teachers as inspectors in the new regulatory regime in England Cambridge Review of Education, 43(4), 467-487.

Brown, A. D. (2006). A narrative approach to collective identities. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 731-753.

Chen, Y., Currie, G., & McGivern, G. (2022). The role of professional identity in HRM implementation: Evidence from a case study of job redesign. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(2), 283-298.

Connelly, M. a. C., J. (1990). Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5 (Jun-Jul 1990)), 2-14.

Handley, D. M. (2005). The Best of Both Worlds: A Former Practitioner Transitions to Life as a Full‐Time Academic. Public Administration Review, 65(5), 624-627.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation: Cambridge university press.

Macfarlane, B. (2022). A voyage around the ideological islands of higher education research. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(1), 107-115.

Suddaby, R., Foster, W. M., & Trank, C. Q. (2016). Re-Membering. The Oxford handbook of organizational identity, 297.

Taylor, S. (2005). Self-narration as rehearsal: A discursive approach to the narrative formation of identity. Narrative Inquiry, 15(1), 45-50.